Political despatches are no longer quite as bloody as that which befell Caesar in Shakespeare’s Roman tragedy, but we have certainly seen several ego-inflated leaders in recent times.

From Trump’s belief in his own infallibility to Johnson’s apparent childhood ambition to be ‘king of the world’ there is no shortage of leaders who like the limelight a little too much.

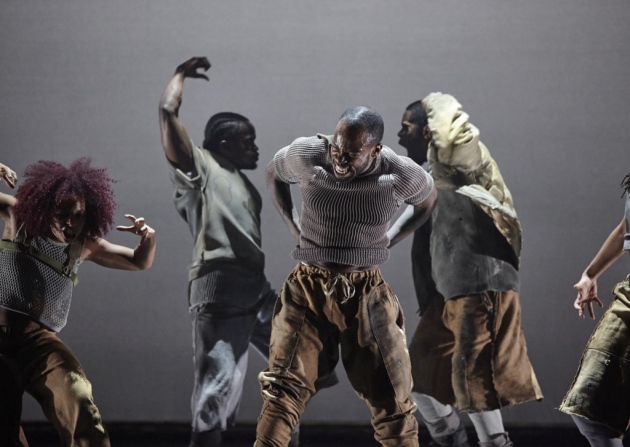

While this new Royal Shakespeare Company of Julius Caesar is bold and adds some modern touches, it doesn’t really lean into its potential contemporary parallels. We get the now seemingly obligatory dance and music prologues with thumping bass with echoes of an old Propeller production, but these feel distant from the main action.

The story itself is relatively traditionally presented. Adjustments and elisions have been made to curtail the cast list but at 20-strong it remains an ambitious production.

Annabel Baldwin gets the majority of attention as Cassius, but they never quite dominate the stage with a fairly neutral version of the lead conspirator. Thalissa Teixeira offers more range as Brutus, but relies too much on hand-sawing than textured emotion.

Nigel Barret’s Caesar, perhaps the titular Shakespeare character with fewest lines, is mercurial in the little time we see him alive. He has more stage time and presence in his ghostly appearances, which seem played partly (and surprisingly) for laughs.

It is William Robinson’s Mark Antony who really stands out, a beacon of passion, oratory, and measured movement. It helps he gets some of the most treasured lines, but that withstanding his performance pits him above the rest of the company. Ella Dacres’ brief appearance as Octavius Caesar also captivates; there is little trouble believing in her steel as a warrior.

The production features a ‘community chorus’ of local people – in Norwich this is made up of Jeneska Alexander, Melissa Bowling, Lucy Daglish, Alice Evans, Helen Wells, Rio Topley, and Rebecca White – but they are given little to do other than glide stoically around the gloomy edges of the large cube that dominates the stage.

Like the revolving central cube, video projections, black blood, and gender-blind casting, these feel like attempts to be different that don’t really have enough significance to transform – or get in the way of – the story.

Ultimately director Atri Banerjee delivers a solid and – stripping away some noisy frippery at the edges – fairly traditional-feeling production, that has enough new to feel interesting but without disturbing the core of the play.

- Julius Caesar continues at Norwich Theatre Royal until Saturday, June 10, 2023.